Imagine what life would be like if a critical service went belly up minutes ago, and you were called in to save the day. You attempt to restart the service, and it just won't give. There are no error messages, but more importantly, no traces of what it was doing before it decided to die. A hundred and one causes course through your mind, and you realize there is no way to know in which direction to go. Maybe you could restart the server altogether. Just maybe.

This scenario is one of the many in which logging can come to your rescue. Usually, a running piece of software keeps a record of important activities related to its running for posterity's sake in a file. Anything can be kept in a log file as it helps developers and sysadmins alike know what happened with a particular piece of software after the fact. Log files are also used by security-oriented persons to review access to particular resources. In networking or messaging, log files record the time messages were sent or received for later reference.

Log files, by definition, keep on increasing in size depending on the frequency and verbosity with which they are updated. To serve their purpose, they are normally opened in append-mode and contain timestamps to help with troubleshooting and forensics. However, this poses a problem as large file sizes make working with log files a cumbersome process for both the system and the human reviewer. Logs are rotated to keep log files tenable. Simply put, a new file is opened while the older one is closed and either kept or deleted depending on design preference. This prevents logs from filling up entire partitions and bringing systems to their knees in the process. You might have noticed log rotation at work on a system nearby. Look at the dates on the boot.log files.

In this case, when a specific condition is met, the current file is renamed by appending a date to identify and track it, and a new file with the original name is opened, ready to receive incoming log messages.

Logging in Linux (rsyslogd)

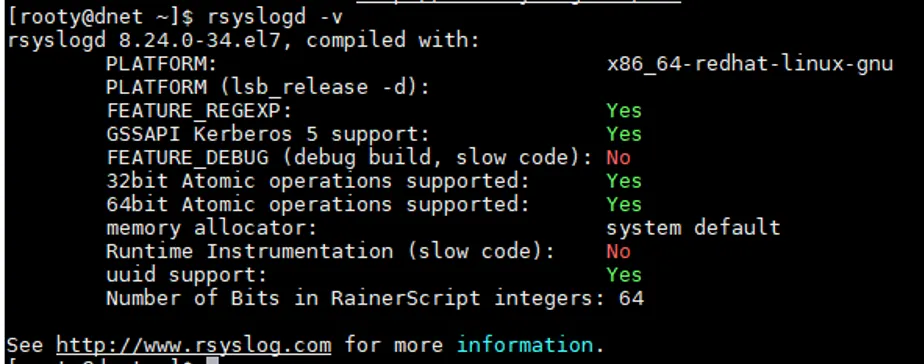

As you might expect, logging in Linux systems, such as the CentOS 7 server I am using for illustration, rely on a daemon to facilitate logging. Rsyslogd is the name of the reliable old service and it is open-source. Actually, it is not so old. It is an improved version of the original syslog daemon, and it possesses the ability to quickly process and forward logs to any location in an IP network. Aside from syslog and rsyslog, there is syslog-ng, which is yet another daemon for handling logs. The default log handler depends on the distro one chooses. Rsyslog comes by default in many Red Hat-based distros. Run the following command to verify its presence and version on your system:

rsyslogd -v

As it is a daemon, you can check that is active by employing systemd as follows:

systemctl status rsyslog

If, for any reason, it is not running, you can start it via systemd.

[ Editor's Note: Many newer systems have replaced rsyslogd with journald for logging. You can choose either option, or even both, to handle your logging needs. For more information, see the documentation for your distribution. This article will assume you are using rsyslogd.]

Logrotate

Logrotate is a Linux utility whose core function is to - wait for it - rotate logs. If it is not installed as part of the default OS installation, it can be installed simply by running:

yum install logrotateThe binary file can be located at /bin/logrotate.

By installing logrotate, a new configuration file is placed in the /etc/ directory to control the general behavior of the utility when it runs. Also, a folder is created for service-specific snap-in configuration files for tailor-made log rotation requests. More on this a bit later.

Daily cron job

A cron job is run daily that starts the utility. This is achieved by placing a call to the utility in the standard cron folder for daily jobs. While the specifics of the call are outside the scope of this article, suffice it to say that the call is just a Bash script that runs the logrotate binary, telling the system what to do in case of an error.

Standard log file location

Logs on a Linux system can be placed anywhere permissions allow. However, due to the fact that they are continually changing in size and content, by definition, the File System Hierarchy prescribes that they are kept in the /var/log/ directory.

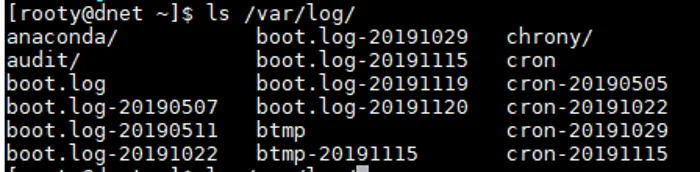

The screenshot below is a peek at the contents of my /var/log directory.

Configuration files and examples

/etc/logrotate.conf

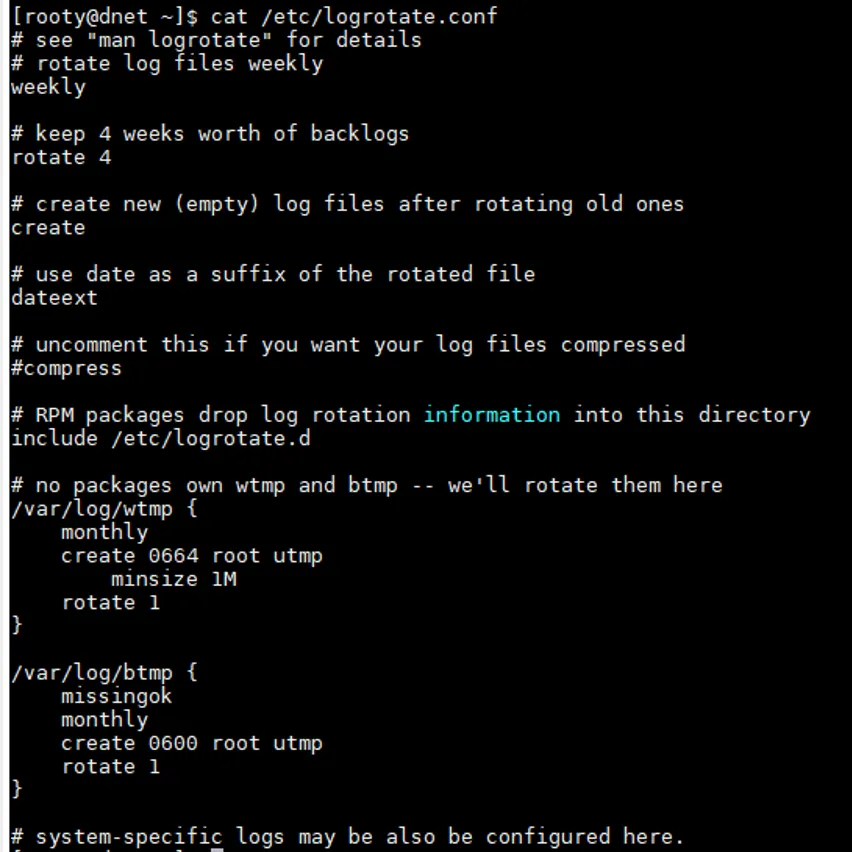

The first file to take note of with regard to the function of logrotate is logrotate.conf. This config file contains the directives for how log files are to be rotated by default. If there is no specific set of directives, the utility acts according to the directives in this file.

Below is a sample of the contents of the configuration file.

Let's go through a few of the directives to get a feel for the flexibility of logrotate. Graciously, the author of the utility has put in enough comments to get a newbie going. You could also see the man page for a deeper dive. The directives weekly, dateext, compress, create, and rotate 4 state that log files are to be rotated weekly, that the date of rotation be used as the identifying suffix of the rotated files, that the rotated files should be compressed, that a new file is to be created to receive incoming logs, and that no more than four logs should be kept. In other words, the fifth newest log should be deleted. Also note that on my system, due to the presence of the # before the compress directive, compression is disabled by default.

Also, there is a directive to include a particular folder: /etc/logrotate.d. This folder is used for package-specific log rotation requests. Packages designed to take advantage of logrotate drop configuration files into this directory. This modularity is in keeping with the Linux spirit and enhances the extensibility of the utility. The configuration files contain similar directives and custom log files where applicable. You can also create your own configuration file to handle any log file of your choosing. Just give the file a name, add the log file to be processed, and place it in this directory. Finally, there are directives for log files with no owner packages, such as wtmp and other system log files. The man page is filled with more directives, and for users who have more specific rotation needs, I strongly advise you to give it a look.

/etc/logrotate.d

Fortunately, I have spoken considerably on the /etc/logrotate.d directory, so without much ado, let me show you the contents of this directory to bring the ideas shared earlier home.

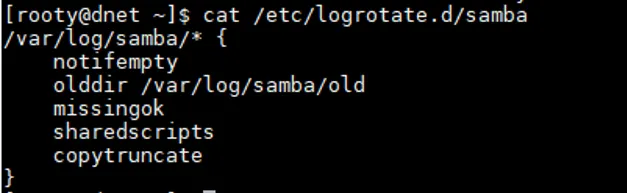

And just for good measure, let's take a look at the Samba configuration file.

Can you spot how similar it is to logrotate.conf? Before I draw curtains on this piece, let's just run through some of the directives in this file:

/var/log/samba/* - The log file to be rotated. In this case, it is every log file in the Samba log directory.

notifempty - Directive stating that the file should not be rotated if it is empty.

olddir /var/log/samba/old - Location to store old rotated logs.

missingok - Stops logrotate from throwing an error if the log file is missing.

copytruncate - Do not close the log file. Make a copy, which will be the rotated, renamed file, and then truncate the log file to zero size

Can you guess what the sharedscripts directive does? No need to guess - consult the man page.

Wrapping up

Hopefully, this is enough to get you up and running with managing logs. Logrotate is a simple yet powerful open-source rotation utility. Till the next post, happy rotating!

[ Free online course: Red Hat Enterprise Linux technical overview. ]

About the author

Edem is currently a sysadmin with a financial services institution where he works primarily with Windows and Linux systems. He also administers VMware Virtualization environments daily. With interests in Automation, IP Telephony, Open Source Alternatives and Information Security, Edem dabbles with technology on any level. He likes to break systems to understand them.

More like this

Browse by channel

Automation

The latest on IT automation for tech, teams, and environments

Artificial intelligence

Updates on the platforms that free customers to run AI workloads anywhere

Open hybrid cloud

Explore how we build a more flexible future with hybrid cloud

Security

The latest on how we reduce risks across environments and technologies

Edge computing

Updates on the platforms that simplify operations at the edge

Infrastructure

The latest on the world’s leading enterprise Linux platform

Applications

Inside our solutions to the toughest application challenges

Original shows

Entertaining stories from the makers and leaders in enterprise tech

Products

- Red Hat Enterprise Linux

- Red Hat OpenShift

- Red Hat Ansible Automation Platform

- Cloud services

- See all products

Tools

- Training and certification

- My account

- Customer support

- Developer resources

- Find a partner

- Red Hat Ecosystem Catalog

- Red Hat value calculator

- Documentation

Try, buy, & sell

Communicate

About Red Hat

We’re the world’s leading provider of enterprise open source solutions—including Linux, cloud, container, and Kubernetes. We deliver hardened solutions that make it easier for enterprises to work across platforms and environments, from the core datacenter to the network edge.

Select a language

Red Hat legal and privacy links

- About Red Hat

- Jobs

- Events

- Locations

- Contact Red Hat

- Red Hat Blog

- Diversity, equity, and inclusion

- Cool Stuff Store

- Red Hat Summit