Every new programming language is created to do something previously impossible. Today, there are quite a few to choose from. But which ones do you really need to know?

This episode dives into the history of programming languages. We recognize the genius of “Amazing Grace,” also known as Rear Admiral Grace Hopper. It’s thanks to her that developers don’t need a PhD in mathematics to write their programs in machine code. We’re joined by Carol Willing of Project Jupyter, former Director of the Python Software Foundation, and Clive Thompson, a contributor to The New York Times Magazine and Wired who’s writing a book about how programmers think.

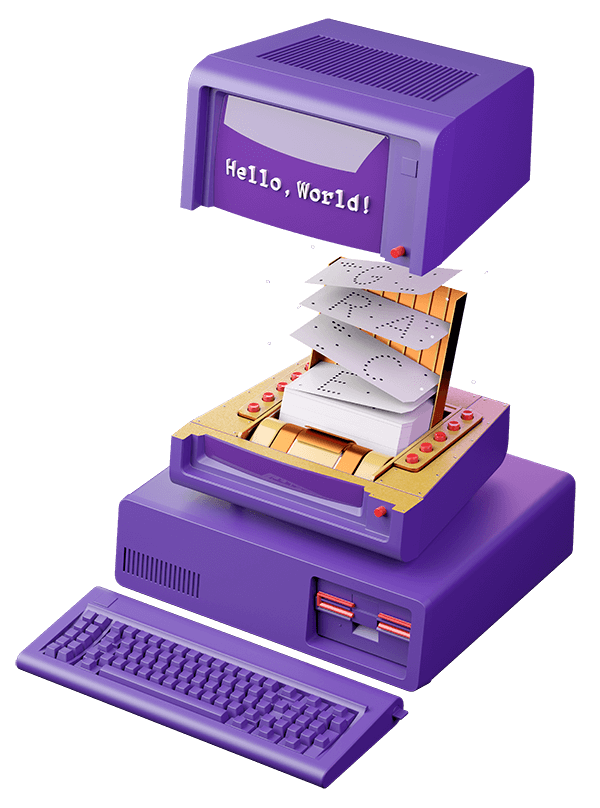

00:07 - Multiple voices

Hello world.

00:12 -Saron Yitbarek

Hello world. Is it signal, or is it noise? All the work we do as developers, all the countless hours of coding and stressing and testing, it all comes down to that one question: are we getting our signal across?

00:29 - Multiple voices

Hello.

00:29 - Saron Yitbarek

Or is our signal lost? Are we just making noise.

00:40 - Saron Yitbarek

I'm Saron Yitbarek and this is season two of Command Line Heroes, an original podcast from Red Hat. In today's episode we're found in translation. It's all about programming languages: where they came from, and how we choose which ones to learn. We're doing a deep dive into the ways we talk to our machines. How those languages are evolving. And how we can use them to make our work sing.

01:08 - Siri

Daisy, daisy, give me your answer true.

01:11 - Saron Yitbarek

If you're a developer like me, you probably feel pressure to be a polyglot, to be fluent in a whole bunch of languages. You better know Java. Better know Python. Go JavaScript, Node. Gotta be able to dream in C++. Maybe know a classic like COBOL, just for cred. And you might even be worrying about a newcomer, like Dart... It's exhausting.

01:36 - Saron Yitbarek

The weird thing is, the computers that we're talking to really only speak one language: machine language. All those ones and zeroes flying by, all those bits. Every single language we learn is, at the end of the day, just another pathway to the same place. It all gets boiled down, no matter how abstracted we are when we're doing the work.

02:03 - Saron Yitbarek

And that's what I want you to keep in mind as our story begins, because we're starting with the moment, the completely brilliant moment, when one woman said: "You know what? I'm a human. I don't talk in bits, I don't think in bits. I want to program using English words."

02:22 - Saron Yitbarek

Might seem like a simple concept today, but once upon a time, that idea, the idea you should be able to talk to a computer in your own way was a joke at best, sacrilege at worst.

02:37 - Saron Yitbarek

Season Two of Command Line Heroes is all about the nuts and bolts that underpin everything we do. And this episode's hero is a woman whose journey you need to know if you want to fully understand our reality. So, I give you: the first lady of software.

02:58 - Speaker 5

Ladies and gentlemen, it's with great pleasure that I present Commodore Grace Mary Hopper. Thank you.

03:02 - Grace Hopper

So I went to Canada to speak at the University of Guelph, and I had to go through immigration at Toronto Airport. And I handed my passport to the immigration officer and he looked at it and looked at me and said, "What are you?"

03:17 - Grace Hopper

And I said, "United States Navy."

03:20 - Grace Hopper

He took a second real hard look at me. And then he said, "You must be the oldest one they've got."

03:28 - Saron Yitbarek

That was Rear Admiral Grace Hopper in 1985. She was 79-years old at the time and delivering her famous lecture at M.I.T.. Even then, Grace Hopper was a legend. She was the god mother of independent programming languages. The woman who used compilers so we could use human language instead of mathematical symbols.

03:51 - Saron Yitbarek

She received the National Medal of Technology, and after she died, the National Medal of Freedom. So: not a slouch. They called her " Amazing Grace."

04:03 - Claire Evans

If anybody was born to be a computer programmer, it was Grace.

04:06 - Saron Yitbarek

That's Claire Evans, a tech journalist and the author of a book called Broad Band, about pioneering women in tech. Evans describes that early word of computers, the one Grace Hopper stepped into in the 1940s when she was a young woman in the Navy Reserves and computers were the size of a small room.

04:25 - Claire Evans

All those early programmers, they were like a priesthood. They were people that were specifically good at something that was incredibly tedious, because this is before compilers, before programming languages, when people were really programming at the machine level, bit by bit.

04:42 - Claire Evans

In order to have the constitution to do that kind of thing, you really have to be a specific kind of person, and Grace really was that kind of person.

04:49 - Saron Yitbarek

Right away, she saw how crazy limiting it was for humans to be using a language meant for machines. It was like trying to walk down the street by telling every atom in your body what to do. Possible? Sure. Efficient? No.

05:06 - Saron Yitbarek

There had to be a shortcut between a programmer's intentions and a computer's actions. Humans had been mechanizing mathematical thinking ever since the abacus. There had to be a way to do that again with computers.

05:19 - Claire Evans

In the past, mathematicians used to have to do all this arithmetic. All this tedious step-by-step work in order to get to the really interesting solutions. And then computers came along and offered the possibility of doing that arithmetic by machine, therefore freeing the mathematician to think lofty, intellectual, systems-oriented thoughts.

05:39 - Claire Evans

Except for, that's not really what happened. Ultimately, the computer came along and then the mathematician had to become a programmer. And then they were stuck once again doing all these bit-by-bit tedious rule-oriented, little calculations in order to write the programs.

05:53 - Claire Evans

So, I think, Grace's perspective on it was she wanted to make sure that computers could assist mathematicians to think great thoughts and do great things without bogging them down in the details.

06:12 - Saron Yitbarek

Hopper was joining a long line of thinkers. You've got Pascal in the 17th century with the first calculator. You've got Babbage in the 19th century with the analytical engine. There's this big, beautiful line of inventors who want to build things to supercharge the human brain. Things that let us process more data than we could ever manage on our own. That's the lineage Grace Hopper was stepping into when she invented something that everybody thought was impossible.

06:42 - Claire Evans

I mean, Grace's idea that people should be able to communicate with their computers using natural language, and that language should be machine independent, therefore interoperable between different computing machines was revolutionary in its time.

06:59 - Claire Evans

People that got behind her, this notion that she called, in the early days, "automatic programming," were considered to be like space cadets in the community of programmers and computer people.

07:12 - Claire Evans

And the people who weren't onboard eventually became known as the Neanderthals, it was this huge rift in the computing community.

07:21 - Saron Yitbarek

Hopper did not have an easy time convincing her superiors to cross that rift. But she saw it as her duty to try.

07:30 - Grace Hopper

There's always a line out here. That line represents what your boss will believe at that moment in time. Now, of course, if you step over it, you don't get the budget. So you have a double responsibility to that line: don't step over it, but also keep on educating your boss so you move the line further out, so next time you can go further into the future.

07:52 - Saron Yitbarek

That future she pushed toward is our present. Pretty much every language that you and I rely on owes a debt to Hopper and her first compiler. So that's space cadets “one”, Neanderthals “zero”.

08:07 - Saron Yitbarek

The idea that we could code not with numbers, but with human-style language. All of a sudden you're typing "Go to Operation 8," or, "Close file C." It was programming made human.

08:21 - Claire Evans

Grace was uniquely aware of the fact that computing was going to be a world changing thing, but it wasn't going to be a world changing thing if nobody understood how to access it or use it. And she wanted to make sure that it was as open to as many people as possible and as accessible to as many people as possible.

08:37 - Claire Evans

And that required a certain level of concession to comprehensibility and readability. So ultimately the desire to create programming languages came from wanting to give more points of entry to the machine and taking it away from this priesthood and opening it up to a greater public and a new generation.

08:59 - Saron Yitbarek

I wanna pause here and just underline something Claire said: programming languages as we know them today come from a desire to open the tech up. To take it away from a priesthood of math PhDs and make development accessible.

09:14 - Saron Yitbarek

The spirit of the compiler that does all that work, it's motivated by a sense of empathy and understanding.

09:21 - Saron Yitbarek

Claire's got a theory about why Hopper was the woman to deliver that change. It has to do with Hopper's work during World War II.

09:29 - Claire Evans

She was doing mine sweeping problems, ballistics problems, oceanography problems. She was applying all of these different, diverse disciplines representing all the violent, chaotic, messy realities of the war and translating them into programs to run on the Mark I computer.

09:45 - Claire Evans

She knew how to do that translation between languages. And I don't mean computer languages, I mean like human languages. She understood how to listen to somebody who was presenting a complex problem, try to understand where they were coming from, what the constraints and affordances of their discipline was and then translate that into something that the computer could understand.

10:06 - Claire Evans

In a way she was like the earliest compiler. Like, the embodied human compiler because she understood that you had to meet people on their level.

10:17 - Saron Yitbarek

Compiling as an act of empathy and understanding. I think we can all keep that in mind when we learn new languages, or wonder why something isn't compiling at all. The compiler's job should be to meet your language where it lives.

10:32 - Saron Yitbarek

Grace Hopper knew that once humans could learn to speak programming languages, and once compilers began translating our intentions into machine language, well, it was like opening the floodgates.

10:43 - Claire Evans

She knew that computing could never develop as an industry, as a world changing force if it was too siloed and too specific. And people who were its practitioners couldn't communicate with the people whose problems needed to be put on the machine, so to speak.

11:00 - Claire Evans

So she was really quite expert at that kind of human translation, which I think, yeah, made her uniquely qualified to be thinking about and creating programming languages.

11:15 - Saron Yitbarek

Hopper's work on English-style data processing language eventually evolved into COBOL, which is sort of perfect, because COBOL is not flashy, it's very down to business, and so was Grace Hopper.

11:28 - Saron Yitbarek

In a way, she gave us a language that sounded a lot like her. Also like Hopper, COBOL's got longevity. It's still around 60 years later.

11:50 - Saron Yitbarek

Okay, so Grace Hopper's compilers were like babelfish, parlaying meaning between programmers and their machines. And they were translating things from higher and higher levels of abstraction.

12:03 - Saron Yitbarek

Then, a few decades later, we get another crucial ingredient added to the language mix. So picture this: the free software community took off in the 1980s, but when the Unix alternative, GNU, was created, there weren't any free and open compilers to go with it.

12:22 - Saron Yitbarek

In order for GNU to give us a real open-source alternative to Unix, in order for programming languages to thrive in the open-source world, the community would need to pull a Grace Hopper — we needed an open-source compiler.

12:38 - Saron Yitbarek

Here's Langdon White, a platform architect at Red Hat talking about where things stood.

12:45 - Langdon White

In the 80s, you can still go spend ten grand pretty easily on a compiler. The free part was a big deal. I don't have an extra ten grand lying around to go buy myself a compiler. Plus the fact that I'd have to buy myself a compiler for every platform I want to target. So, in those days it was mostly Unix, but all the different flavors.

13:06 - Langdon White

So you wouldn't be able to just buy one, you would also have to buy multiple for different architectures or different vendors.

13:14 - Saron Yitbarek

Langdon notes that it was more than just costs at stake. In some cases, it was the coding work itself.

13:21 - Langdon White

People don't realize that it matters how you structure your code in very specific ways. So doing nested for loops or doing nested while loops or that kind of thing may be okay, depending on the compiler.

13:38 - Langdon White

So, you know, if you don't know how it's optimizing your code it's very, very difficult to know how to write your code to get the most optimization.

13:49 - Saron Yitbarek

Suffice to say, we needed a free option, an accessible option, a trustworthy option. What we needed was the GNU C compiler, the GCC. That was the beast, first released in 1987, that merged Grace Hopper's compiler revolution with the free software movement.

14:12 - Saron Yitbarek

It standardized things and let everybody compile what anybody else had written. The richness of our languages is thanks to that moment.

14:22 - Carol Willing

The fact that the GCC was open sort of moved languages to a different level.

14:29 - Saron Yitbarek

Carol Willing works at Project Jupiter, and she's the former director of the Python Software Foundation.

14:35 - Carol Willing

People started realizing that proprietary languages, while they served a purpose at the time, they weren't going to gain the acceptance and adoration of the developer community. Because if I'm a developer, I'm going to want to learn what is most commonly used and as well as what is new and on the forefront.

14:59 - Carol Willing

I don't necessarily want to develop a skill that will lock me into one technology. I think one of the reasons that Python was so successful is it was open source, it had a very clean syntax.

15:11 - Carol Willing

What it was doing is it was allowing people in a common way to solve problems quickly, efficiently. And to also allow people to collaborate. And I think those are the signs of good programs and good libraries is: if you can get your work done with a minimum amount of headache and you can share it with others. I think that's golden.

15:35 - Saron Yitbarek

Over the years, the GCC evolved to support Java, C++, Ada, Fortran, I could go on.

15:43 - Carol Willing

By having a common underlying interface like the GCC, it lets people take languages and then customize them to their particular needs. For example, in the Python world, there's many different libraries and even specifically in the scientific Python world, we've got things like numpy, and scikit-image, scikit-learn.

16:08 - Carol Willing

And each of those had sort of a more specific task that they are known for. So, we've also seen things like bioinformatics and natural language processing. And so people are able to do many different things working off a common base. But then putting elements into their languages or libraries that allow them to optimize problem solving in their particular industry or area.

16:42 - Saron Yitbarek

So, this is what happens when compiler technology runs headfirst into the open source movement, right? Over time, the collision creates a big bang of new community-supported languages that anybody can learn and build with.

16:58 - Saron Yitbarek

There are hundreds and hundreds of those languages being used today.

17:03 - Carol Willing

As open source became more popular and more accepted, what we've seen is a proliferation of languages. There are a number of languages around cell phone technology and mobile. Different languages that help make game development more straightforward. All purpose languages, like Python and Ruby that were sort of foundational for the web development and delivery of web applications and websites.

17:34 - Saron Yitbarek

The list goes on. And, yeah, that Tower of Babel we're building is just going to get more packed in the future. But look, you can also see it as a cornucopia, a language feast. And we're going to help you sort through that feast — next.

17:55 - Saron Yitbarek

Okay, so I know where the language flood came from. But how do we make sense of it all? How do we pick out languages that matter to us? It's a big question, so I brought in some help: Clive Thompson's one of the best writers out there for making sense of the tech world. He's a columnist at Wired, a contributing writer at the New York Times Magazine, and he's working on a book now about the psychology of computer programmers.

18:24 - Saron Yitbarek

Which is perfect, because we need to know what's going on in our brains when we choose which ones to learn.

18:31 - Saron Yitbarek

Here's me and Clive hashing it all out.

18:35 - Saron Yitbarek

When I was first starting out as a new developer, I just said, "Lemme find the best one, I'm going to get really good at it. And then I'll be done."

18:44 - Saron Yitbarek

But it's not quite that simple. Why are there so many programming languages?

18:49 - Clive Thompson

Each language has sort of a bias of things that it's good at. So, typically, the reason that someone creates a new language is there's something they want to do that existing languages aren't good for. JavaScript is a good example of that.

19:03 - Clive Thompson

Netscape had created a browser back in the mid '90s and all these web masters wanted to do something a little more interactive. They wanted there to be a way to have a bit of scripting inside their website.

19:16 - Clive Thompson

And so these demands were coming to Netscape. And they were like, "Alright, we need, there's nothing out there that can do this, we need a scripting language that we build inside our browser."

19:25 - Clive Thompson

And so they hired Brendan Eich, who was considered a senior guy. He was like 32, and everyone else was like 21.

19:32 - Saron Yitbarek

That's senior in developer world.

19:35 - Clive Thompson

And they gave him ten days to make JavaScript. So he literally just didn't sleep for ten days and he frantically cranked out a scripting language. And it was kind of ungainly and kind of a mess. But it worked. And it allowed people to do very simple things, it had buttons and dialogs and popups and whatnots.

19:54 - Clive Thompson

And so that's an example of a language that came, was created to do something that wasn't really possible at that point in time.

20:01 - Saron Yitbarek

That's fascinating.

20:03 - Clive Thompson

So that's why so many languages exist, is that people keep on finding a reason to do something that no one else can do.

20:11 - Saron Yitbarek

So what is so interesting to me about the relationship between developers and our programming languages is we have such a strong attachment to these tools, why is that?

20:22 - Clive Thompson

There's a couple reasons why. One is that sometimes it's literally just an accident of what was the first language that you learned. And it's kind of like your first love.

20:30 - Clive Thompson

And I think it's also like different personalities work with different types of languages. Like, you look at Facebook, and it was designed using PHP. And PHP is kind of a hairball of a language. It's very irregular. And it sort of grew in these fits and starts. And that's sort of the way Facebook feels, too.

20:49 - Clive Thompson

In comparison, the guys at Google decided, "We want a super high performance language, because Google, at Google we're all about things running really fast, and things, sustaining trillions of users at once."

21:02 - Clive Thompson

And so they decide to make Go, and Go is a really terrific language for that sort of high-performance computing.

21:08 - Saron Yitbarek

Let's go a little bit deeper. Is it that I, as a developer, with my specific personality, am going to be naturally attracted to certain languages? Or that the language I work in might influence my personality?

21:25 - Clive Thompson

Well, definitely both. But I do think that there is a really strong resonance that people find when they hit a language that they like. You go to a computer science curriculum and you sort of learn what you have to learn: they're all teaching Java. Sometimes more JavaScript or Python.

21:46 - Clive Thompson

But the point is, you're forced to learn it, so you learn it. But what do people do when they have the choice? And this is where you really see how the sort of emotional or psychological style of someone gravitates towards a language, because I talked to one guy who tried learning JavaScript a bunch.

22:03 - Clive Thompson

And it was just sort of, it's kind of an ugly language to look at. It's got the curly bracket nightmare going on. And so he tried and failed and tried and failed and tried and failed. And then one day he saw a friend working in Python. And it just looked so clean and beautiful to him. He was kind of a writer, and it's often regarded as a writerly type of a language, because the indentation makes everything easy to read.

22:28 - Clive Thompson

And it just clicked with him, because there was just something about the way that Python worked and looked, it's beautiful sparseness, that hit him.

22:39 - Saron Yitbarek

So, talking with Clive I realized there are languages that are thrust upon us. I'm talking about those ancient languages that are just baked into everything we work with — the code Latin.

22:53 - Saron Yitbarek

But there're also languages we choose, the languages that fit our personalities. And if you want to know what's new and shaking things up, you want to ask a developer what they use on the weekend.

23:05 - Saron Yitbarek

Here's more of our conversation:

23:08 - Clive Thompson

So when I ask people: "What are you doing in your spare time?" It'll be all this weird stuff. I think it's actually one of the things that sort of, you know, nice and laudatory about developer behavior is that they tend to be very curious people.

23:22 - Clive Thompson

I know people that decided, "I'm going to learn Erlang, just for the hell of it."

23:26 - Saron Yitbarek

I'm trying to imagine these projects that people are working on on the weekends. And it's almost like the project is secondary. It's like the learning of the tool, the language, is more important. That's really what they're there for.

23:41 - Clive Thompson

Exactly. This, is sort of why you'll see people just constantly re-iterating over and over again these calendaring and to-do list things because it's a very quick way, just to figure out, yeah, what does this language do and how does it work and it almost doesn't matter what I'm building, so long as I'm building something.

23:56 - Clive Thompson

They want to know what it feels like to think in that language. Is it going to be, is it going to feel easy, and thrilling and fluent in a way that I'm not experiencing with the current languages? Is it going to open up doors to make things easier to do?

24:13 - Clive Thompson

So there's a possibility space that occurs when you encounter a new language that can be really exciting. Imaginatively exciting.

24:20 - Saron Yitbarek

So I'm a Ruby, a very proud Ruby on Rails developer, I think it was about two years ago that another pretty well known Ruby developer, Justin Serrals, did this really great talk advocating for this idea that a language doesn't need to be sexy to be used.

24:41 - Saron Yitbarek

And his thesis, his whole point was that Ruby was really exciting because it was new. And it kind of got to a point about a couple years ago where it just didn't need any more things. It was done. It was a stable language, it was a mature language, and, as a result of it being mature, it's not as exciting for developers. It's not this new toy to play, and so we kind of slowly moved away from it on to the next shiny thing.

25:05 - Saron Yitbarek

So, in a sense, it's almost our own curiosity that might kill a language, or make it a little more stale, independent of whether the language is actually good or bad.

25:18 - Clive Thompson

I think that's absolutely true. In fact, the downside of this deep curiosity and desire to self-educate that you see amongst developers is that they're constantly trying to find the new shiny thing. And use that language to replicate things that are already basically done pretty well by other languages.

25:37 - Saron Yitbarek

Right.

25:37 - Clive Thompson

So that's that. Curiosity is a benefit and a trap.

25:43 - Saron Yitbarek

Yeah, beautifully put.

25:49 - Saron Yitbarek

Sometimes our curiosity may be a trap. But it's also the thing that fuels the evolution of languages. Every new language is created because someone said, "What if?" They come about because that developer wanted to do something different.

26:06 - Saron Yitbarek

They wanted a whole new way of saying it.

26:08 - Grace Hopper

And I'll promise you something.

26:11 - Saron Yitbarek

I think Grace Hopper deserves a last word here.

26:15 - Grace Hopper

Just during the next 12 months, any one of you says that we've always done it that way, I will instantly materialize beside you and I will haunt for 24-hours. And see if I can get you to take another look. We can no longer afford that phrase, it's a dangerous one.

26:34 - Saron Yitbarek

The story of Grace Hopper and the first compiler reminds us that there's always a better way to do something if we can just find the words.

26:43 - Saron Yitbarek

And, no matter how abstract those languages become, whether we're floating high or low over the ones and zeroes of machine language, we need to make sure it's a smart choice. We choose the language, or maybe even build the language that helps our intentions come closer to reality.

27:03 - Saron Yitbarek

If you want to learn more about languages and compilers, you are not alone. We pulled together some super useful material to help you dive deeper. And it's all waiting for you in our show notes. Check it out at redhat.com/commandlineheroes.

27:20 - Saron Yitbarek

Next episode, we're tracking the complicated path toward making open-source contributions. What are the real life struggles of maintainers? How do we make that very first pull request?

27:32 - Saron Yitbarek

We're taking you through Contributing 101.

27:39 - Saron Yitbarek

Command Line Heroes is an original podcast from Red Hat. Listen for free on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, or wherever you do your thing.

27:48 - Saron Yitbarek

I'm Saron Yitbarek, until next time keep on coding.

Keep going

The Importance of a Nanosecond: Remembering Grace Hopper

Grace Hopper inspired many engineers. Here’s one story of a young developer lucky enough to see her in person.

How many programming languages have you used?

Machines speak one language—but we humans speak to machines in so many ways.

Command Line Heroes: The Game

This week’s post: How open source game development hones valuable skills. Gaming languages, gaming in open source, and Open Jam.